As I mentioned in this post, when I heard Art De Vany say he eats “two meals a day, sometimes one, sometimes none” I thought that was unfathomable.

But after reading The Obesity Code and The Complete Guide to Fasting, in which Dr. Jason Fung described his experience with his Intensive Dietary Management clinic and how he would get many patients with type 2 diabetes off insulin and diabetes medications within just a few weeks through extended fasting, Lisa and I were ready to give it a try.

Neither of us had even been diagnosed as prediabetic, but Lisa’s fasting blood sugar had been 102 in October 2016, which is what got us started on this dietary and lifestyle journey.

In The Obesity Code, Dr. Fung cited a study of 70 days of alternate daily fasting in which body weight was decreased by an average of 6%, while fat mass decreased by 11.4%, with no loss of lean mass. He also said

Studies of eating a single meal per day found significantly more fat loss, compared to eating three meals per day, despite the same caloric intake. Significantly, no evidence of muscle loss was found.

The Obesity Code, p. 243, Jason Fung, M.D.

It’s important to note that with alternate daily fasting, you’re still eating every day. Typically you eat dinner every evening, and skip breakfast and lunch every other day.

So on Sunday you would eat all three meals, but then on Monday skip breakfast and lunch, limiting yourself to water, black coffee or tea. Then repeat the cycle.

Two Three important additional points:

- If you are taking insulin or medications for diabetes, you absolutely need to have medical supervision while fasting to prevent dangerous low blood sugar episodes.

- If you’re eating lots of carbohydrates, you will be miserable on an all-day fast. It’s best to get at least somewhat converted to fat metabolism before starting fasting. Eggs, meat, avocados, nuts and other foods relatively high in fats and with moderate protein, combined with limiting carbs to 25-40g per day, will help convert your body to burning fat.

- I’m not a doctor. I’m not giving medical advice. Check this out for yourself and make your own decision in consultation with medical professionals you trust.

One more tip: a good way to start is with time-restricted feeding, just skipping breakfast every day and eating lunch and dinner during a 6-8 hour window. This still gives you an extended period of lowered insulin levels, and isn’t quite as extreme as going 24 hours without food.

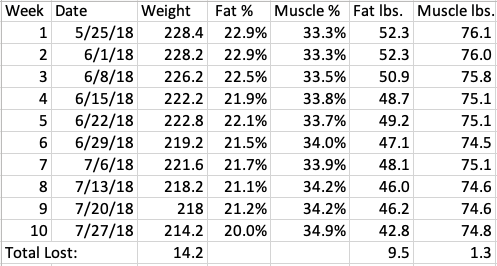

With all of those caveats, here are my weekly bluetooth scale readings from our 10 weeks of alternate daily fasting. I weighed every day, but for simplicity am just sharing the Wednesday morning readings.

With the caveat that the body fat and muscle percentages seem to be calculated by some voodoo electrical signals running through the soles of my feet, at least all of those readings were coming from the same scale.

So the bottom line is that I lost about a pound of fat per week while essentially preserving muscle mass. (The other 4 lbs. lost, according to the scale, were water weight .)

Note also that when we started the 10-week experiment I was already down 37 lbs. from Peak Lee, as demonstrated in my “before” pictures. So presumably I had already lost the “easy” weight.

And in keeping with the study cited by Dr. Fung, my body weight was reduced by 6.2%, while my body fat was reduced by 18.1%, during the 10-week period.

Have you tried intermittent fasting or time-restricted feeding?

If so, how did it work for you?

If not, what questions do you have?

See the whole series about my health journey. Follow along on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.