It was 11 years ago today that Mayo Clinic announced formation of the Mayo Clinic Center for Social Media (MCCSM) and the Social Media Health Network (SMHN), which eventually became the Mayo Clinic Social Media Network (MCSMN).

As MCSMN is sunsetting Saturday, this post is the next in my series looking back at its origins, growth and legacy, and also recognizing those who contributed so much to bring the social media revolution to health care.

Once we got approval in principle for an expanded social media effort at Mayo Clinic in early 2010, I began convening brainstorming and planning sessions to outline what “bigger and bolder” should look like.

Most of those discussions were internally focused, and included colleagues from various Mayo Clinic departments, divisions and functions. The vision we were developing was to encourage strategic application of social media not just in external communications and marketing, but also in clinical practice, research and education.

We had been using social media tools for a few years to do our media relations work more effectively. Our task force’s role was to set up what became MCCSM, to serve as a resource to our Mayo colleagues throughout the organization so they could do likewise in their work.

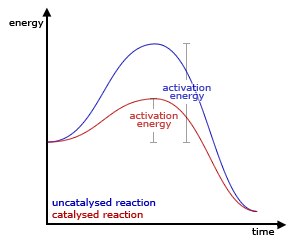

To use a chemistry metaphor, we wanted to be a catalyst. A catalyst reduces the activation energy in a chemical reaction. By developing guidelines and best practices, along with a strong enterprise-level presence on the major social networks, we would make it easier for our Mayo Clinic colleagues to embrace and apply social media. We would work out the kinks and also resolve some of the issues that might otherwise hinder them.

We would reduce the “hump” they would have to get over.

Extending this principle was the idea behind SMHN, a sibling organization to MCCSM. As we were developing helpful resources and programs in social media for our Mayo staff, we saw SMHN as a way to make them available to colleagues elsewhere, while also recovering some of the development costs through paid memberships and event registrations.

Even more important from my perspective was the reality that we were all trying to figure out this health care social media landscape, and by convening SMHN and recruiting an External Advisory Board (EAB) for MCCSM we could rally smart people into a movement where we could learn together.

The folks I mentioned in part 1 of this series were essentially the proto-EAB, and Reed Smith’s perspective through the Texas Hospital Association and his wife’s experience with The Studer Group was particularly helpful. Andy Sernovitz’s example in creating The Blog Council (now socialmedia.org), a group of the leaders of social media in large organizations, made me think perhaps there was a place for a similar gathering of representatives from hospitals of all sizes.

Mayo Clinic had joined The Blog Council, and as we created SMHN the goal was to extend services and education not only to the leaders of social media in smaller hospitals, but also to clinical and research champions interested in health care social media.

Our vision was first to equip our Mayo Clinic staff, then to equip the social media equippers in other organizations, and finally to support clinicians and researchers who might be the lone early social media advocates. Mayo Clinic’s sponsorship provided some “air cover” (switching from chemistry to military metaphors) that helped advocates sell the legitimacy of social media to their leaders.

Mayo Clinic’s announcement of MCCSM and SMHN on July 26, 2010 was met with significant interest and even excitement. That meant we needed to immediately get about the business of recruiting a team and also building out our EAB.

I’ll recount that story tomorrow.